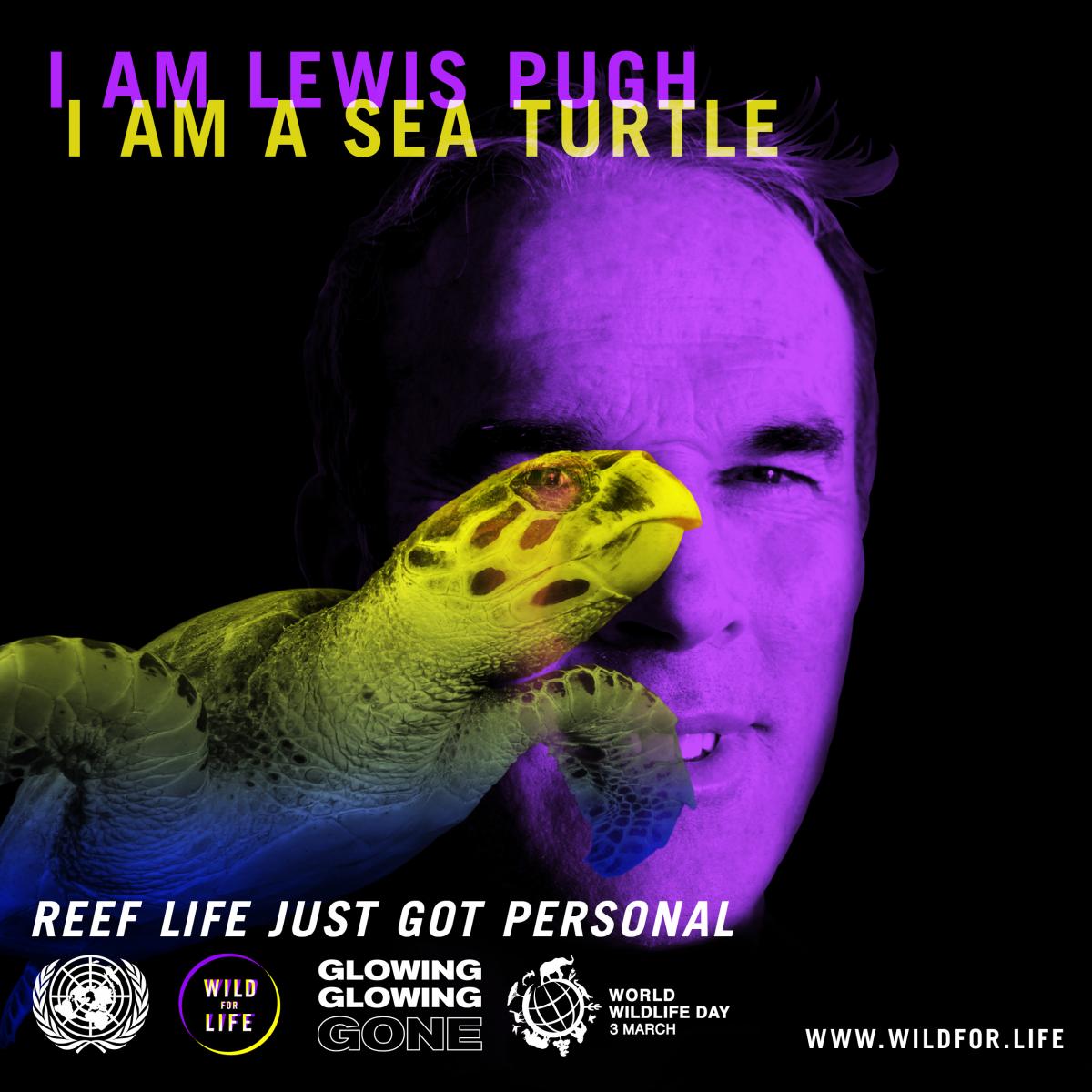

Q&A with UNEP Patron for Protected Areas, Kristine Tompkins, and Oceans, Lewis Pugh

According to the latest Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services assessment, 75% of land, 66% oceans and 85% of our planet’s wetlands have been negatively impacted by human activity. UN reports are also raising alarm bells on the climate crisis and tipping points from which we may not be able to rehabilitate our planet’s ability to deliver life supporting vital goods and services.

To build knowledge on how nature functions to deliver goods and services to humanity, UNEP’s Wild for Life 2.0 campaign will bring users on an interactive journey to learn about 4 distinct ecosystems- marine, peatlands, savannas and forests - why they are crucial to human well-being, why they are under threat and what we can do to help.

For this journey, we feature an incredibly unique ecosystem that is found across the globe but may be the least explored of all the planet’s natural wonders: The Peatlands. This unique ecosystem has been working since the beginning of time to filter fresh water, nurture medicinal plants, protect land from floods and capture and store enormous quantities of carbon. In fact, though they cover only 3% of the planet’s surface, they store twice as much carbon than all the world’s forests combined!

The setting for Wild for Life 2.0’s interactive Peatlands journey are globally significant peatlands such as the Peatland of Peninsula Mitre in the Southern Cone of South America. The Tierra del Fuego archipelago represents the southernmost part of the Magellanic peatland (moorland). The main island, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, is divided between Chile in the west and Argentina in the east. Oceanic conditions and the SW wind direction prevail in southern Tierra del Fuego, where a west-east aligned mountain range dominates the landscape.

You both have been to this incredibly remote and unique part of the world. You both are also on the front line of advocating for protected areas and taking care of nature so that it can take care of us. In addition to your work with Tompkins and Lewis Pugh Foundations, you are respectively the Patron for Protected Areas and Oceans. Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts on why this area should receive greater protection.

UNEP: Kristine, you’ve protected and rewilded millions of acres in Chile and Argentina. How were you originally inspired to do this?

Actually, in 1992 my husband Douglas Tompkins was the one who fully realized that we could participate in the global conservation movement by creating public-private conservation projects with the end result of establishing new national parks in Chile and Argentina. So, one can say that I was inspired by my husband’s capacity to imagine creating large-scale permanently protected areas. Since we began, Tompkins Conservation has not stopped creating new parklands and rewilding these areas in both countries.

UNEP: Lewis you have advocated for marine protected areas in the Polar Regions. Why do you risk your life in this endeavour?

I've spent over 30 years swimming in the oceans, and I have seen them change dramatically. The biggest changes have been in the Polar Regions where I’ve witnessed warming seas, retreating glaciers, melting permafrost and the disappearance of sea ice. These changes will impact every person and the whole of the animal kingdom. Climate change will accelerate rapidly if we don’t protect crucial ecosystems like peatlands, which capture so much carbon. I can’t just stand by and watch it unfold.

UNEP: How did you come to know and love this remote area?

Kristine: When Douglas was training as a ski racer in the early 1960’s in Chile and Argentina he got to know the Southern Cone fairly well. I followed in the early 1990’s, and we both fell in love with the region, but more importantly, we saw that the diversity of landscapes, from the temperate rainforests of what's now Pumalin Douglas Tompkins National Park, to the expansive grasslands of Patagonia. More recently, in the face of severe climate change, we are focusing on the importance of peatlands, especially in Chilean and Argentine Tierra del Fuego. As an example of this, Peninsula Mitre, with almost 84% of Argentina's peatlands, is especially key as the most important carbon capture point in the country.

Lewis: Most of my Antarctic expeditions have left from Patagonia. So that’s where I do my final cold-water training. The Beagle Channel is the perfect place to train for a swim in Antarctica. The water is icy cold, but not so cold that it’s impossible to train. The Darwin icefield, whose glacial tips reach the sea level in the fiords of both the Beagle Channel and the Straits of Magellan, is located here.

Every time I pass through Patagonia I tell myself I need to spend more time here, it is just so beautiful! I strongly support linking land and sea based protected areas such as what is being proposed in the peatlands of the Peninsula Mitre.

UNEP: What is the stand out moment in all you have done?

Kristine: Oh, this is quite difficult to say! Certainly, the final national park donations eighteen months ago in Chile, the largest conservation donation in history, has to stand as one of them, but we are fortunate to have met most of our large conservation goals over the last 28 years. I am always proud of our teams and the relationships we have forged with governments in every single case!

Lewis: It would have to be helping to establish the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area in Antarctica. The swim I did there in 2015, to highlight the importance of protecting this sea, was my toughest ever – not to mention the coldest! Afterwards I had to shuttle between various capitals for 2 years to get the final agreement approved. It was exhausting. But the Ross Sea is one the most important ecosystems on the planet. At 1.5 million km2 the Ross Sea MPA is now the largest protected area in the world. To put it in perspective, it’s the size of the UK, France, Germany and Italy combined.

UNEP: How can ordinary people find their own agency to make transformational change?

Kristine: The first, and perhaps most difficult step, is simply deciding to join in the movement to change our relationship to nature, and to form more healthy, dignified communities. Without this commitment, we will slide back down into inaction very quickly.

As in all things in life, one has to commit to something and never let it go - in this case, get out of bed every single day and do something for those things you love, those things you hold to be true. There are millions of people who work in conservation and each and every one of us is ordinary, but we are committed to doing our part. We’re well past the point where doing nothing is acceptable!

Lewis: It starts with becoming environmentally literate, so that we understand the impact of our actions on the world around us. For example, every purchase you make is a decision about the future you want to leave for your children. The food we eat, the clothes we wear, the way we travel, the way we build and heat our homes – all have an impact.

I think it is also important to spend time in nature. We only protect the things we love, and you can't help but love the natural world when you take the opportunity to witness how truly miraculous it is.

UNEP: What’s next on the horizon for your work?

Kristine: We have many new projects underway protecting land and sea in Chile and Argentina and, of course, we have certain commitments to a few past projects that keep us busy as well. We are often asked, “What will you do next?”, and I can tell you that the urgency of the climate crisis and the extinction crisis only grows every single day. We are propelled to work even faster, on a larger-scale and with greater determination than ever.

Lewis: Right now, my team and I are focussed on helping build a network of marine protected areas around Antarctica, to protect the region from the kind of industrial overfishing that has decimated other oceans, and to help mitigate against the impacts of climate change.

These protected areas will be in East Antarctica, the Weddell Sea and the Antarctic Peninsula. Together with the Ross Sea MPA, they will protect over 4 million km2 of vulnerable ocean. It will involve considerable work and diplomacy, as the 25 nations who govern Antarctica, all have to agree to it. But I am absolutely determined to help get the incredible part of the world properly protected.